Need Help?

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Sign up for our

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

Need Help?

CONTACT US

CONTACT US

Let’s Meet in the Middle

Filed Under: Couples Therapy, Relationships

In This Article…

We all want our feelings to be understood. But even if we have a significant other with whom we feel understood, we may find that we become misaligned as career and family life evolve and change. Nowhere is this more true than with professional couples and dual-career families as they take on new role-based challenges.

Recent research¹ indicates that the dynamics affecting the quality of a couple’s relationship stem from differences in motivation (approach/avoidance orientations) and patterns of interpersonal behavior. I look at both factors in the case of Meg and Paul, two highly educated professionals, each with histories of neglect in childhood. What I also consider is a style of engagement that seems well-matched to the experience and expectations of professional couples.

I believe we can learn a great deal from working through our issues—their causes, course, and resolution—as couples. Doing so not only makes us happier in our couples, it makes us smarter managers, leaders and collaborators in the workplace. But of course, these truths can seem rather remote when we are in the throes of relational conflict and cannot yet see a pathway forward.

Being heard, in this context, is more than an auditory task, and it involves more than an exchange between therapist and patient. When therapists listen actively, they provide a hearing for all three persons in the room. As the therapist and couple together reflect upon this active listening process, the couple notices how different it is than what normally happens in their exchanges at home. Thus, safety and learning depend upon how the therapist facilitates, moderates and contains the listening process.

In my practice, I work mostly with professional couples, the same demographic I’ve served for over 25 years in my executive coaching practice. When it comes to helping relationships, they seem to welcome an active, norm-setting agent who is willing to reign in behaviors that threaten conditions of safety and openness, or that derail productive engagement. Their basic ego strength is usually adequate. They tend to default to a practical sense of urgency to “fix” things. While their impatience and an action bias can impede progress, initially I find it helpful to leverage these attitudes to generate motivation.

They may be more skeptical and scared than they’re willing to admit, but they know they need help. They haven’t found a way to do it themselves. So, the therapist must find ways to intervene early, to validate their decision to seek therapy, and to change the way they communicate and interact. When we can model a tolerance for conflict and an ability to notice and discuss how their polarized attitudes and behaviors operate reciprocally to sustain conflict, we earn credibility. And that’s critical. Professional couples more than others will be looking for evidence that we’re competent.

Meg was a fighter with an excitable temperament and a penchant for order and control. Both had suffered neglect, but Paul had taken a route of pathological accommodation and escape, while Meg had gone the way of rebellion and escape. Neither had healed the wounds of neglect. As their lives became more complicated by a third child, increased financial demands, chronic patterns of conflict and naïve hopes gave way to long-standing vulnerabilities, and each sought individual therapy.

Meg sat stern-faced with arms crossed as he spoke, casting dismissive glances his way as he struggled to express himself. There was eye-rolling too, which caused me to wonder how far he got in speaking his mind at home. It was all she could do to limit her dissent to nonverbal communications as Paul spoke. Then, when it was her turn, Meg’s voice rose in angry criticism. Her first aim was to correct Paul. As she flushed with anger, Paul went pale with fear.

She was taken aback and flushed from red to rose as a sudden pause prevailed. Paul sat quietly, still pale, anxiously awaiting the next steps. I can imagine the reader might wonder about the force of my presence and the effects of my behavior. Most of my clients (consulting practice) and patients (clinical practice) describe me as down-to-earth, caring, sincere and constructive. Even in my most direct moments I believe they recognize a positive intent in my face, words, and actions.

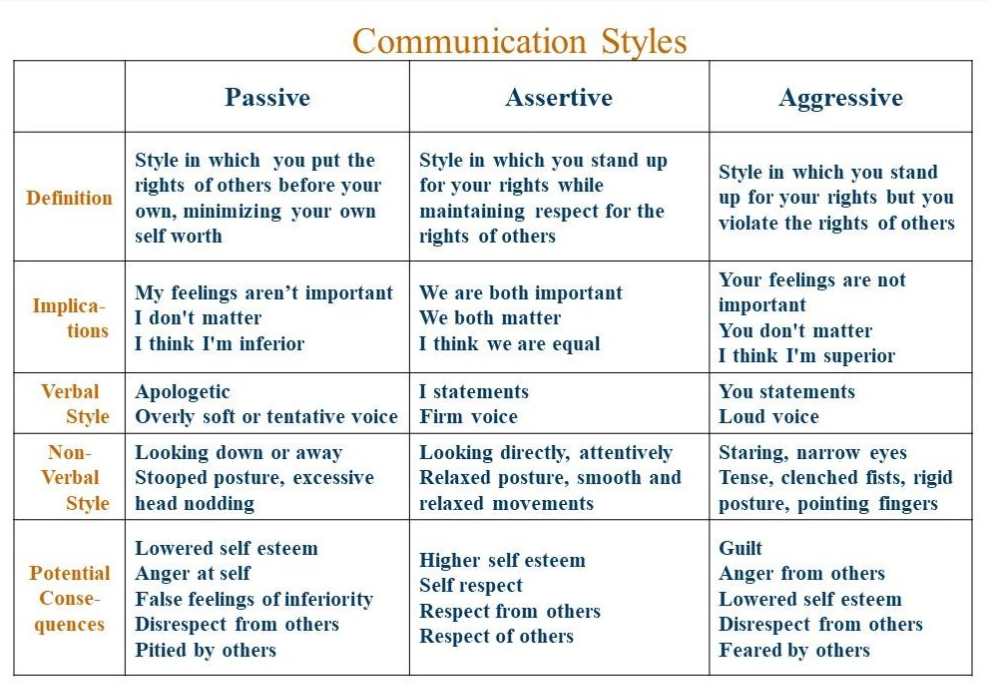

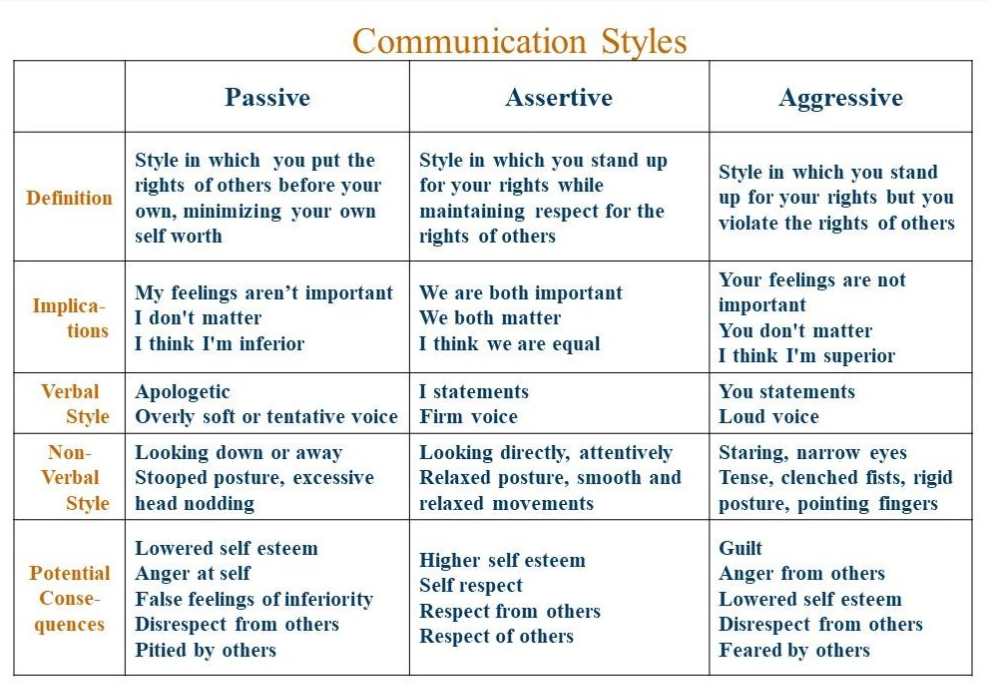

I expressed a grounded confidence. I assured them that they need not accept nor reject anything I said too quickly. I encouraged them to simply consider how it might be relevant for them. My tone with Meg and Paul was neither harsh nor timid. It was not aggressive; it was assertive. It was not out of control; it was tempered and composed. My first intervention was to invoke norms of propriety in the consulting room. This atmosphere of civility became the defining quality of dyadic communication in the therapy.

After the “flareup” was extinguished, discussion resumed. I asked how representative this episode was of the problems they’d been experiencing. They admitted that it was all too common. The difference was that at home Paul would usually not get the initial words out. Rather, Meg would define the violation Paul had committed (being late or forgetting an errand), and he would go quiet, retreat for a while, and then later try to explain himself and perhaps become defensive.

Meg would later remark on how being with Paul was like having another child. Paul didn’t agree with this characterization, but fighting it only meant extending the quarrel. So, he usually quit at this point, believing it was not worth the pain and wouldn’t change the outcome anyway. The more she played the role of his parent, the more he was cast in the role of a child.

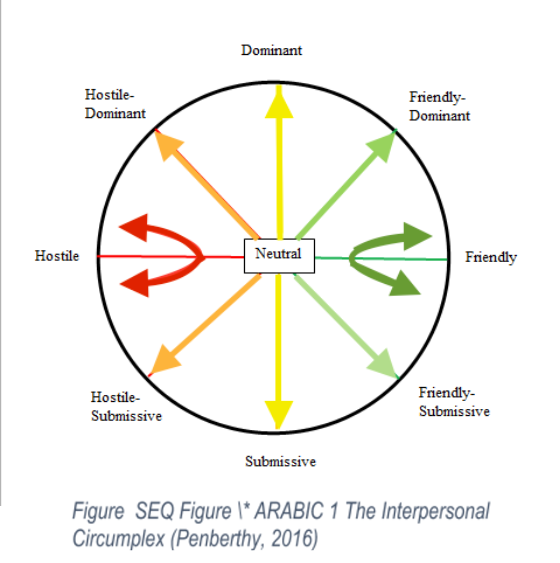

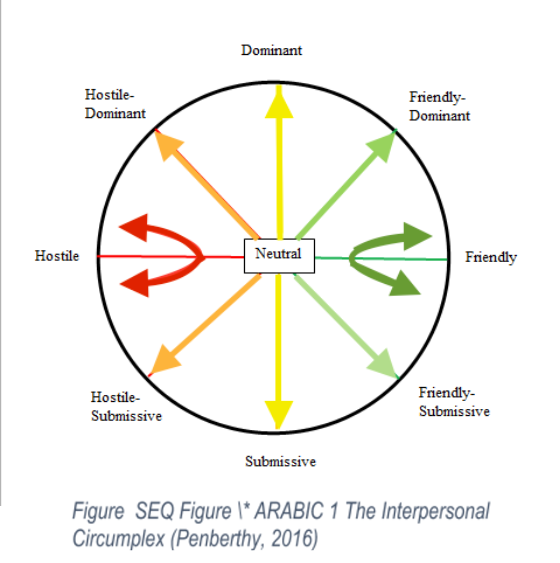

We used the interpersonal circumplex² to consider this chronic pattern. I have found this model quite useful with couples. It plots interpersonal behavior in two-dimensional space using two axes, Dominant/Submissive and Friendly/Hostile. Using the model, we’re able to see how our expressed behavior is likely to “pull” a style of behavior from others. On the one hand, a dominant expression tends to pull a submissive response, and a submissive expressive style pulls a dominant response. On the other hand, friendly and hostile expressions seem to invite others to respond in suit. So, how did this apply to Meg and Paul?

They had been interacting in the hostile side of the circumplex, Paul from the submissive area (passive style) and Meg from the dominant area (aggressive style). We also observed that my intervention came from the friendly dominant area (assertive style). Finally, we noticed that the pause arose from the “neutral” space in the middle of the circumplex as a pause for reflection on communication style. Thus, the title of this article and my suggestion to couples that when they notice tension building, and before it becomes entrenched conflict, they tell themselves that it may be time to “meet in the middle.”

Such successes in adaptive learning and development promote an approach orientation. This includes beliefs that most problems can be solved with help, and that those with whom we share our lives at home and at work are usually willing and able to be helpful. We act from a benevolent hypothesis about others’ motivations and with optimistic beliefs about what we can do with their help. But absent this positive early-life experience, we may approach relationships with less trust and positivity, with more suspicion or doubt, and often with fears of abandonment.

For Meg, it was an ostensibly kind and service-oriented father (pastor) who seemed to have little time and interest for her needs. He turned his attentions elsewhere, perhaps in ways that won him esteem in the eyes of those he helped. And her hopes of finding enduring love with her first husband failed. Like her father, he was “selfish.” And now, as life’s demands on Paul increased, she saw him too as neglecting her out self-interest. It was reinforced daily when he arrived home late or forgot to stop at the market.

Meg had been on alert for signs of neglect since she was a little girl, all to guard against more rejection, and she found them in her adult relationships with men. We could describe this motivational orientation as avoidance. She might ask Paul to do things, but her expectations of his delivering on these requests were very low. She was fully armed to express her anger and mistrust of him every time he fell short. In her eyes, he was breaking a promise, and she wasn’t taking it anymore. She increasingly threatened divorce in her moments of peak anger and frustration.

Paul’s mode of avoidance was more obvious. It was based on his fear of conflict learned as a child. Meg’s stern look and voice tone signaled a threat to which he reacted with an impulse to retreat. Neither he nor Meg could readily identify in the moment the fears and vulnerabilities they were replaying from childhood. They were both caught up in self-protective (defensive) routines intended to distance them from harm. That is, until in session we would enter the neutral zone represented on the circumplex model.

Noticing and suspending the visceral grip of legacy, avoidance-based emotions and motivations, adaptive approach-oriented motivations, goals, and behaviors became available. This pause simply hastened access to the approach-based responses that had been activated in Paul after Meg finally collapsed in emotional exhaustion and despair from her angry outbursts. Meg’s approach behavior was activated as she finally welcomed Paul’s concern, support, and sympathy when her aggressive energies had quieted. They both took roundabout routes to dialogue.

It took concrete behavioral analysis of specific situations to shift their focus to variables that they could realistically influence or control. We had to do a great deal of situation analysis in our therapy sessions to acquire a basis of trust and positive expectations for change. We had to recognize the way they were both setting unrealistic and unattainable goals, and how they were neglecting adequate attention to the positive thoughts and behaviors that could interrupt their old routines.

Finally, we had to notice how different the results of our in-session problem solving were from their out-of-session efforts, and to ask ourselves why they were different. They recognized that there was little they were not able to do behaviorally if they approached it deliberately and thoughtfully. They had to own the responsibility for doing this work, and they had to recognize the payoff in doing the work, individually and as a couple.

They internalized a capacity for assertive problem solving that extended beyond the consulting room and their relationship, and into the workplace. Meg reported less ruminating, guilt and resentment. Paul described a growing sense of confidence and ease in his interactions with Meg. They regressed on occasion and learned how to grow from the experience. They deepened their insight and skills in the process of repairing one or two significant ruptures along the way.

I accommodated their sense of practical urgency by anchoring change efforts in concrete behaviors and specific situations. In this way, they were able to more readily see the behaviors that help and hinder realization of their change goals. They learned to appraise and re-appraise their expectations for change against standards of what was realistic and achievable. In the process, they noticed how slowing down for a reflective pause could speed things up. They found reason for hope in these skilled practices.

Through early steps of progress in session and practical guidance for change between sessions, they acquire skills and build trust and confidence in the therapist and in each other. Guidance may be more directive in the early phase of therapy, but it becomes more non-directive as positive norms of attitude and behavior take effect. As an easier, less defensive quality of exchange becomes possible, the role of the therapist becomes more that of consultant and coach.

Couples’ gains are sometimes achieved in waves over longer periods of time (6 months or more). For others, significant change, for example restructuring relational dynamics and communications, might occur in 6-8 weeks. And when does it stop? That too varies, but insofar as our work is goal-focused, we are better able to jointly assess how they are doing, what they’ve learned, and when termination or transition to a maintenance schedule might be advisable.

I have found that goals and commitments are most robust when they’re grounded in the personal truth we can only obtain from rigorous assessment. That’s why our assessment must be a joint process. Couples must play an active role in interpreting the data that I help them collect, including the patterns of behavior that I help them surface in our sessions. Couples must personally discover the power of meeting in the middle, in that neutral zone of reflection. It is there that defenses melt away and the consequential costs and benefits of change can be seen. In that way, we soon acquire a call to action—“Let’s meet in the middle”—which can give us reason to halt the cycle of escalating conflict and see things as they really are.

References

1. See for example Kuster, M., Bernecker, K., Bradbury, T. N., Nussbeck, F.W., Martin, M., Sutter-Stikel, D., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). Avoidance orientation and the escalation of negative communications in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 262-275

2. Thanks to Kim Penberthy for permission to use her version of the circumplex model: Penberthy, J. Kim (2016). Effective Treatment for Persistent Depression in Patients with Trauma Histories: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP). Paper presented at the meeting of Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) Conference, Philadelphia, PA.

For further information on the circumplex model, it’s history and use, see Horowitz, L., Wilson, K.R., Turan, B., Zolotsev, P., Constantino, M., & Nenderson, L. (2006). How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: A revised circumplex model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 67-86.

© 2019 Psychotherapy.net LLC

Recent research¹ indicates that the dynamics affecting the quality of a couple’s relationship stem from differences in motivation (approach/avoidance orientations) and patterns of interpersonal behavior. I look at both factors in the case of Meg and Paul, two highly educated professionals, each with histories of neglect in childhood. What I also consider is a style of engagement that seems well-matched to the experience and expectations of professional couples.

Couples Issues

By the time strain and conflict have become chronic, partners have often done a good deal of blaming and fault-finding with one another. It doesn’t help, but it’s almost unavoidable, as people lose their capacity to see things as they really are. Only later, after bumping up against the reality that they are stuck and that it's probably not entirely their or their partner’s fault, might they conclude that outside help, objectivity and perspective are needed.I believe we can learn a great deal from working through our issues—their causes, course, and resolution—as couples. Doing so not only makes us happier in our couples, it makes us smarter managers, leaders and collaborators in the workplace. But of course, these truths can seem rather remote when we are in the throes of relational conflict and cannot yet see a pathway forward.

By the time strain and conflict have become chronic, partners have often done a good deal of blaming and fault-finding with one another

Even with awareness of our need for help, we retain the need to protect ourselves against being found lacking. We may privately hope that a therapist will take our side and that we’ll be vindicated. Couples are often ambivalent, wanting perspective but simultaneously maintaining defenses. Disarming them is about eliminating threats to emotional safety and ensuring that each person has the chance to be heard. To satisfy these conditions, we must be an empathic and assertive mediating presence.Being heard, in this context, is more than an auditory task, and it involves more than an exchange between therapist and patient. When therapists listen actively, they provide a hearing for all three persons in the room. As the therapist and couple together reflect upon this active listening process, the couple notices how different it is than what normally happens in their exchanges at home. Thus, safety and learning depend upon how the therapist facilitates, moderates and contains the listening process.

Individual or Couples Therapy

There are times when individual therapy prior to or in addition to conjoint therapy may be indicated. When either or both members of the couple suffer from an acute mood disorder or chronic mental health problems, their capacity to participate in couples therapy may be limited. And sometimes they just can’t believe that something different and good can come from discussing their issues with their partner, not yet. But I’ve found that they’re likely to underestimate their readiness to participate in couples therapy.In my practice, I work mostly with professional couples, the same demographic I’ve served for over 25 years in my executive coaching practice. When it comes to helping relationships, they seem to welcome an active, norm-setting agent who is willing to reign in behaviors that threaten conditions of safety and openness, or that derail productive engagement. Their basic ego strength is usually adequate. They tend to default to a practical sense of urgency to “fix” things. While their impatience and an action bias can impede progress, initially I find it helpful to leverage these attitudes to generate motivation.

They may be more skeptical and scared than they’re willing to admit, but they know they need help. They haven’t found a way to do it themselves. So, the therapist must find ways to intervene early, to validate their decision to seek therapy, and to change the way they communicate and interact. When we can model a tolerance for conflict and an ability to notice and discuss how their polarized attitudes and behaviors operate reciprocally to sustain conflict, we earn credibility. And that’s critical. Professional couples more than others will be looking for evidence that we’re competent.

Meg and Paul

When I met Paul, he was presenting with anxiety stemming from work and marriage. He was on an SSRI for anxiety and on Ritalin for ADHD. He reported a childhood replete with dysfunction and less than good-enough parenting. Raised in a small town in Alabama, he adapted by retreating to a rich imagination and creative talents, later attending a top art school in the Northeast and then settling in Brooklyn. I didn’t have to tell him his family of origin was dysfunctional. He knew it and ran as fast as he could to escape it.Paul had taken a route of pathological accommodation and escape, while Meg had gone the way of rebellion and escape

Soon, it became clear that adapting at work (from artist to manager) was not nearly as challenging as making things work at home with Meg. Like Paul, Meg had a history of insecure attachment, growing up in a pastor’s home in rural Connecticut. After a failed marriage that produced two boys, she met and married Paul, who hadn’t had much success in dating or sexual intimacy. She, too, was bright and won a scholarship to an Ivy League college, but she had responded differently to childhood issues.Meg was a fighter with an excitable temperament and a penchant for order and control. Both had suffered neglect, but Paul had taken a route of pathological accommodation and escape, while Meg had gone the way of rebellion and escape. Neither had healed the wounds of neglect. As their lives became more complicated by a third child, increased financial demands, chronic patterns of conflict and naïve hopes gave way to long-standing vulnerabilities, and each sought individual therapy.

The Circumplex Emerges

When Meg and Paul came in for their intake interview, the tension was almost immediately manifest. Sitting at either end of my six-foot sofa, they made no attempt to conceal the distance that had grown between them. I asked them to tell me what caused them to seek therapy at this time and suggested that Paul, the meeker of the two, talk first. He spoke carefully, haltingly at times, always rounding if not blunting the point of the issues he raised. I conjured an image of one navigating a minefield.Meg sat stern-faced with arms crossed as he spoke, casting dismissive glances his way as he struggled to express himself. There was eye-rolling too, which caused me to wonder how far he got in speaking his mind at home. It was all she could do to limit her dissent to nonverbal communications as Paul spoke. Then, when it was her turn, Meg’s voice rose in angry criticism. Her first aim was to correct Paul. As she flushed with anger, Paul went pale with fear.

This atmosphere of civility became the defining quality of dyadic communication in the therapy

Her fault-finding with Paul was peppered with global accusations prefaced by “you never” and “you always.” She painted a picture of his inconsiderateness, broken promises and selfishness. Neglected as a child, she suffered it again in her marriage to Paul. Her voice rose well above the norms for my office–yes, I have such norms. So, I intervened. With a hand gesture signaling a timeout, I said, “Meg, do you have any idea how overwhelming your energy is right now?” She halted and I continued, “You’ll have to turn it down a bit if we are to communicate.”She was taken aback and flushed from red to rose as a sudden pause prevailed. Paul sat quietly, still pale, anxiously awaiting the next steps. I can imagine the reader might wonder about the force of my presence and the effects of my behavior. Most of my clients (consulting practice) and patients (clinical practice) describe me as down-to-earth, caring, sincere and constructive. Even in my most direct moments I believe they recognize a positive intent in my face, words, and actions.

I expressed a grounded confidence. I assured them that they need not accept nor reject anything I said too quickly. I encouraged them to simply consider how it might be relevant for them. My tone with Meg and Paul was neither harsh nor timid. It was not aggressive; it was assertive. It was not out of control; it was tempered and composed. My first intervention was to invoke norms of propriety in the consulting room. This atmosphere of civility became the defining quality of dyadic communication in the therapy.

After the “flareup” was extinguished, discussion resumed. I asked how representative this episode was of the problems they’d been experiencing. They admitted that it was all too common. The difference was that at home Paul would usually not get the initial words out. Rather, Meg would define the violation Paul had committed (being late or forgetting an errand), and he would go quiet, retreat for a while, and then later try to explain himself and perhaps become defensive.

Meg would later remark on how being with Paul was like having another child. Paul didn’t agree with this characterization, but fighting it only meant extending the quarrel. So, he usually quit at this point, believing it was not worth the pain and wouldn’t change the outcome anyway. The more she played the role of his parent, the more he was cast in the role of a child.

We used the interpersonal circumplex² to consider this chronic pattern. I have found this model quite useful with couples. It plots interpersonal behavior in two-dimensional space using two axes, Dominant/Submissive and Friendly/Hostile. Using the model, we’re able to see how our expressed behavior is likely to “pull” a style of behavior from others. On the one hand, a dominant expression tends to pull a submissive response, and a submissive expressive style pulls a dominant response. On the other hand, friendly and hostile expressions seem to invite others to respond in suit. So, how did this apply to Meg and Paul?

They had been interacting in the hostile side of the circumplex, Paul from the submissive area (passive style) and Meg from the dominant area (aggressive style). We also observed that my intervention came from the friendly dominant area (assertive style). Finally, we noticed that the pause arose from the “neutral” space in the middle of the circumplex as a pause for reflection on communication style. Thus, the title of this article and my suggestion to couples that when they notice tension building, and before it becomes entrenched conflict, they tell themselves that it may be time to “meet in the middle.”

Figure 2 Communication Styles (Penberthy, 2016)

About Motivation

Of the many ways to characterize motivation, a fundamental way of conceptualizing it is through the approach/avoidance paradigm. It’s been around since Neo-Freudian thinkers like Karen Horney, Erik Erikson and Harry Stack Sullivan, and builds upon the interpersonal point of view. It gained even more support from the observational studies of mother-infant attachment. Its central thesis is that we are essentially social beings with needs for connection and intimacy. As adults, these needs manifest in our intimate relationships with others, and also in our interdependency in the workplace.What we learn early in life from caregiver relationships shapes our beliefs and expectations about what is possible and probable

What we learn early in life from caregiver relationships shapes our beliefs and expectations about what is possible and probable. When our caregivers are attentive and available, and as we and they learn how to jointly navigate nonverbally and pre-cognitively in ways that satisfy our needs, we develop a sense of trust: “I can rely on others to care, to read my behaviors, and when they fail, they don’t abandon me. No, they persist until my needs or insecurities are resolved.”Such successes in adaptive learning and development promote an approach orientation. This includes beliefs that most problems can be solved with help, and that those with whom we share our lives at home and at work are usually willing and able to be helpful. We act from a benevolent hypothesis about others’ motivations and with optimistic beliefs about what we can do with their help. But absent this positive early-life experience, we may approach relationships with less trust and positivity, with more suspicion or doubt, and often with fears of abandonment.

Patterns of Avoidance

In the case of Meg and Paul, we observed histories of maltreatment that would understandably lead to lower expectations of what might be possible in relationships. They might look for (project) evidence of the betrayal and mistrust they experienced early in life in the contemporary behaviors of those they hoped would be there for them.For Meg, it was an ostensibly kind and service-oriented father (pastor) who seemed to have little time and interest for her needs. He turned his attentions elsewhere, perhaps in ways that won him esteem in the eyes of those he helped. And her hopes of finding enduring love with her first husband failed. Like her father, he was “selfish.” And now, as life’s demands on Paul increased, she saw him too as neglecting her out self-interest. It was reinforced daily when he arrived home late or forgot to stop at the market.

Meg had been on alert for signs of neglect since she was a little girl, all to guard against more rejection, and she found them in her adult relationships with men. We could describe this motivational orientation as avoidance. She might ask Paul to do things, but her expectations of his delivering on these requests were very low. She was fully armed to express her anger and mistrust of him every time he fell short. In her eyes, he was breaking a promise, and she wasn’t taking it anymore. She increasingly threatened divorce in her moments of peak anger and frustration.

Paul’s mode of avoidance was more obvious. It was based on his fear of conflict learned as a child. Meg’s stern look and voice tone signaled a threat to which he reacted with an impulse to retreat. Neither he nor Meg could readily identify in the moment the fears and vulnerabilities they were replaying from childhood. They were both caught up in self-protective (defensive) routines intended to distance them from harm. That is, until in session we would enter the neutral zone represented on the circumplex model.

Noticing and suspending the visceral grip of legacy, avoidance-based emotions and motivations, adaptive approach-oriented motivations, goals, and behaviors became available. This pause simply hastened access to the approach-based responses that had been activated in Paul after Meg finally collapsed in emotional exhaustion and despair from her angry outbursts. Meg’s approach behavior was activated as she finally welcomed Paul’s concern, support, and sympathy when her aggressive energies had quieted. They both took roundabout routes to dialogue.

they had to recognize the payoff in doing the work, individually and as a couple

These, then, were the dispositional tendencies of motivation that energized their chronic patterns of conflict. The avoidance-based mindset had governed behavior with increasing frequency. I noticed that the approach-based resolution strategies were not working as often or as well. They were both feeling exhausted and discouraged. Both, especially Meg, were losing hope that things could change. Their differences in personality and behavior seemed unchanging, perhaps unchangeable.It took concrete behavioral analysis of specific situations to shift their focus to variables that they could realistically influence or control. We had to do a great deal of situation analysis in our therapy sessions to acquire a basis of trust and positive expectations for change. We had to recognize the way they were both setting unrealistic and unattainable goals, and how they were neglecting adequate attention to the positive thoughts and behaviors that could interrupt their old routines.

Finally, we had to notice how different the results of our in-session problem solving were from their out-of-session efforts, and to ask ourselves why they were different. They recognized that there was little they were not able to do behaviorally if they approached it deliberately and thoughtfully. They had to own the responsibility for doing this work, and they had to recognize the payoff in doing the work, individually and as a couple.

Getting to the Point

The advantage of couples therapy for Meg and Paul was that it made them more responsible and accountable sooner. Their contributions to the problems were noticed and called out in real time. Faster-acting avenues of change became available. My observations were grounded in specific situations. It’s an approach that safeguarded them both and returned our focus to salient themes of reciprocal interaction that underlies their conflicts. Concrete "do’s and don’ts” emerged as takeaways.They internalized a capacity for assertive problem solving that extended beyond the consulting room and their relationship, and into the workplace. Meg reported less ruminating, guilt and resentment. Paul described a growing sense of confidence and ease in his interactions with Meg. They regressed on occasion and learned how to grow from the experience. They deepened their insight and skills in the process of repairing one or two significant ruptures along the way.

Disposition does not mean “chipped in stone.”

Disposition does not mean “chipped in stone.” Their differences in temperament (Paul more laid back and Meg more intense) remained. However, both discovered a greater sense of freedom from the automatic expression of their avoidant motivations. They learned that their reactive tendencies from early life were important to notice (somatically, emotionally, cognitively, relationally). These tendencies were not to be dismissed, denied, or taken as fact; rather, they became valued as warning signs.I accommodated their sense of practical urgency by anchoring change efforts in concrete behaviors and specific situations. In this way, they were able to more readily see the behaviors that help and hinder realization of their change goals. They learned to appraise and re-appraise their expectations for change against standards of what was realistic and achievable. In the process, they noticed how slowing down for a reflective pause could speed things up. They found reason for hope in these skilled practices.

Concluding Reflections

Each couple is unique, and the helping strategies of their therapists will vary in approach, length of treatment, and frequency and duration of sessions. Having said that, I usually tell couples that it will take us 4-6 weeks to determine if couples therapy is working for them. By then, we’ll have a good idea of what the core issues are and what is required to address them. And we’ll do that by actively engaging the couple in the process, which means they’ll be more able to make informed decisions.Through early steps of progress in session and practical guidance for change between sessions, they acquire skills and build trust and confidence in the therapist and in each other. Guidance may be more directive in the early phase of therapy, but it becomes more non-directive as positive norms of attitude and behavior take effect. As an easier, less defensive quality of exchange becomes possible, the role of the therapist becomes more that of consultant and coach.

Couples’ gains are sometimes achieved in waves over longer periods of time (6 months or more). For others, significant change, for example restructuring relational dynamics and communications, might occur in 6-8 weeks. And when does it stop? That too varies, but insofar as our work is goal-focused, we are better able to jointly assess how they are doing, what they’ve learned, and when termination or transition to a maintenance schedule might be advisable.

Couples must personally discover the power of meeting in the middle, in that neutral zone of reflection

My approach to helping others as a coach and therapist has always been assessment-based and goal-oriented. Goals in this sense represent purposive aims that give meaning to our actions and accomplishments. These are considerations that weigh heavily in the hearts and minds of most professionals. When these “stakes” are called out in terms of the people they want to be and what’s required to realize these aims, I’ve usually gotten their attention. And after a good deal of experimentation with new skills at home and at work, their attention is firmly planted in interpersonal space, knowing more than ever that success at home and at work is about relationships.I have found that goals and commitments are most robust when they’re grounded in the personal truth we can only obtain from rigorous assessment. That’s why our assessment must be a joint process. Couples must play an active role in interpreting the data that I help them collect, including the patterns of behavior that I help them surface in our sessions. Couples must personally discover the power of meeting in the middle, in that neutral zone of reflection. It is there that defenses melt away and the consequential costs and benefits of change can be seen. In that way, we soon acquire a call to action—“Let’s meet in the middle”—which can give us reason to halt the cycle of escalating conflict and see things as they really are.

References

1. See for example Kuster, M., Bernecker, K., Bradbury, T. N., Nussbeck, F.W., Martin, M., Sutter-Stikel, D., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). Avoidance orientation and the escalation of negative communications in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 262-275

2. Thanks to Kim Penberthy for permission to use her version of the circumplex model: Penberthy, J. Kim (2016). Effective Treatment for Persistent Depression in Patients with Trauma Histories: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP). Paper presented at the meeting of Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) Conference, Philadelphia, PA.

For further information on the circumplex model, it’s history and use, see Horowitz, L., Wilson, K.R., Turan, B., Zolotsev, P., Constantino, M., & Nenderson, L. (2006). How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: A revised circumplex model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 67-86.

© 2019 Psychotherapy.net LLC

Bill Macaux, PhD, MBA, has two parallel areas of practice that center on one population: professionals and executives. As a coach and consulting psychologist, he held leadership roles with RHR International, a global management psychology consultancy, and Right Management. He developed the first research-based assessment of executive presence (the Bates ExPI). In recent years, however, he has allocated more time and attention to working with couples and individuals in his Providence-based clinical practice. He believes, like John Dewey, that "We don't learn from experience, we learn from our reflection on experience." He has found this adage to be particularly apt when his clients are feeling stuck and at a crossroads in their relationship. His recent work in the consulting arena has focused on adaptive development in the face of growing role-based challenge and change. Please visit his website and whitepapers of interest: Leader Identity Development and Navigating at the Inflection Point.

Bill Macaux, PhD, MBA, has two parallel areas of practice that center on one population: professionals and executives. As a coach and consulting psychologist, he held leadership roles with RHR International, a global management psychology consultancy, and Right Management. He developed the first research-based assessment of executive presence (the Bates ExPI). In recent years, however, he has allocated more time and attention to working with couples and individuals in his Providence-based clinical practice. He believes, like John Dewey, that "We don't learn from experience, we learn from our reflection on experience." He has found this adage to be particularly apt when his clients are feeling stuck and at a crossroads in their relationship. His recent work in the consulting arena has focused on adaptive development in the face of growing role-based challenge and change. Please visit his website and whitepapers of interest: Leader Identity Development and Navigating at the Inflection Point.