Despite prevailing evidence that exposures are an effective (if not, the most effective) component of treatment for child anxiety disorders¹, therapists might reasonably feel reluctant to implement this therapeutic strategy in their practice. “By design, and simply stated, exposures make children with anxiety feel more anxious”. How, then, can they be used to treat anxiety? This seems counterintuitive. I certainly thought so when I first started my training as a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and as a child-anxiety therapist. However, through my training, I learned more about the rationale that underlies the efficacy of exposures, and continuously witnessed the benefits of exposures firsthand through my own clinical work. Through this process, I transitioned from an exposure-skeptic to a strong believer.

Exposures, Anxiety & Children

“Exposures” are clinically created and controlled scenarios that involve introducing an anxiety-evoking image or experience in a graded fashion so that individuals can learn how to regulate and manage their anxiety response to a feared stimulus or situation. For example, if a child has a fear of the dark, then an “exposure” would involve having the child sit in a dark room. Exposures are effective because they allow anxious children the opportunity to learn through their own experience that what they fear will happen (e.g., a monster will pop out from a dark corner) does not actually happen. After repeated practice experiencing the feared event or image while building coping responses, the child learns that the feared situation (e.g., dark room) is no longer associated with danger (e.g., because a monster never popped out of the corner). Some children learn this after only one or two exposures, other children require more practice. Additionally, exposures allow children the opportunity to “sit in” their anxious feelings and learn how to tolerate them by letting uncomfortable, anxious feelings come and go. Many children initially think that if they confront a feared situation, their anxiety levels will skyrocket and never come back down. Exposures allow children the opportunity to learn that although their fear levels will likely increase when confronting a feared situation, over time (i.e., as they learn that nothing “bad” or “dangerous” is happening), their fear levels will eventually come back down—and usually within a few minutes.

In my clinical experience, exposures work best when they are implemented gradually. I wouldn’t have the child sit in a pitch-black room by himself for 20 minutes at the second or third treatment session. This is called “flooding” and may have detrimental effects. Instead, I might start with having the child sit in a room with dim lighting for 30 seconds, and then gradually move up in time and darkness level week-by-week until the child reaches his treatment goal (which in this case, might be to fall asleep alone at night with the lights off).

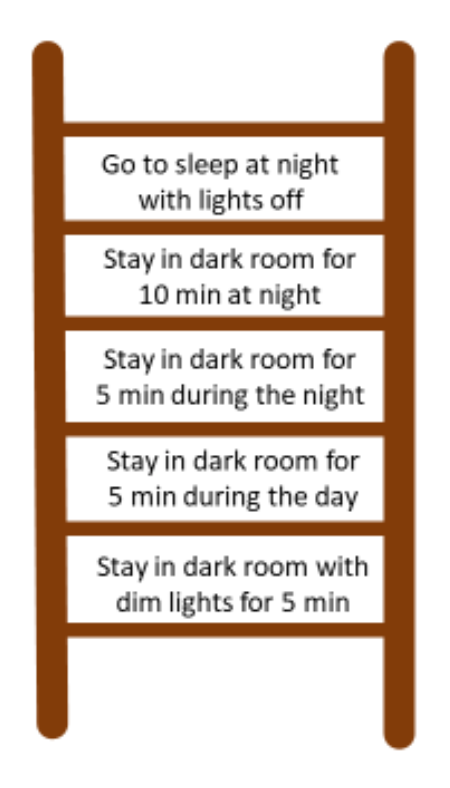

Exposures should also be planned in advance and agreed upon by all parties. The child (and parent) should know what’s coming and should play a collaborative role in planning the exposures. This is often done by creating a “fear ladder” wherein the child, parent, and clinician determine a treatment goal (e.g., to be able to fall asleep alone with the lights off) which is at the top of the ladder, and then plan “steps” to reach that goal (in the form of gradual exposures).

Example fear ladder that I created:

In addition to being gradual and planned, exposures should be frequently practiced. The more practice the child has with exposures, the easier (i.e., less scary) the exposures will get. More practice with the exposures allows for more opportunities to realize that the feared situation is not truly dangerous. Therefore, exposures should ideally be conducted both in-session and at-home as “therapy homework.”

Furthermore, given that one of the main purposes of anxiety treatment is to improve the child’s use of coping skills when facing feared events, exposures should be taught and delivered alongside active coping skills. Other coping skills include relaxation strategies (e.g., slow, controlled breathing; progressive muscle relaxation) and thought switching (i.e., identifying negative, anxious thoughts and switching them to neutral or positive thoughts). These skills should be practiced before and during the exposures, and are meant to facilitate the regulation of the child’s fears as s/he sits through the exposure. Coping skills teach the child that “I have some control of my scary feelings” and exposures teach the child that “Nothing bad happened, even though I thought it would.” Together, these practices work to reduce anxiety in children.

Common (and Reasonable) Myths

The prospect of conducting exposures in treatment sessions can be daunting for therapists, particularly beginning clinicians. At first, I, too, had reservations. What if these exposures make my patients’ anxiety worse? What if my patients despise me for putting them through distress and they never return again? How am I supposed to convince children that confronting the things they’re extremely afraid of will actually help them?

To my relief, I am not alone in having experienced these concerns, as other therapists, according to Stephen Whiteside and his colleagues², have reported feeling reluctant about exposures for similar reasons. Over time, however, I have come to learn that although these concerns are shared and understandable, they are actually myths, or perhaps in the lingo of practice, irrational thoughts.

Myth #1: Exposures Make Anxiety Worse

The proper delivery of exposures involves the following three steps:

- The child confronts a feared situation (increase in anxiety)

- Nothing “bad” or “dangerous” happens (decrease in anxiety)

- The child realizes that what s/he was afraid was going to happen did not end up happening (return to zero anxiety)

Given that proper exposure delivery involves steps 2 and 3, exposures do not make anxiety worse. Rather, exposures help children learn that the feared situation is not associated with real danger, which leads to reductions in anxiety, and often a sense of pride and accomplishment for successfully facing their fears. A potential concern might then be, “Well, what if something bad does happen during the exposure?” This is an understandable concern (one I admittedly had), but perhaps not a reasonable one. For example, let’s say the child with the dark phobia hears a noise while he is in the dark room. At first, he may interpret this as something “scary” happening, which one might reason would lead to an increase in anxiety during the exposure and subsequent maintenance of the dark phobia. However, upon examining the situation more closely, the therapist can guide the child into realizing that even though the child perceived the noise as something “scary” or “bad” happening, nothing bad actually happened. Did the noise itself cause the child any danger? What other (non-scary) thing could the noise have been?

Another important lesson here is that even though something dangerous happening during an exposure is possible, that does not mean that it is probable (this is also a lesson that we teach our patients!). Just like it is possible for us to get into a car accident any time we get into a car, it is not highly probable; therefore, we should not let the possibility of a car accident prevent us from ever getting into a car. This is because the benefits of car transportation (i.e., the ability to get around to wherever we want, whenever we want) outweigh the slight risk involved. Similarly, we should not let the possibility of something bad happening during an exposure prevent us from delivering exposures to our patients. There is a much stronger likelihood that the exposure will be successful, which will lead to major anxiety reductions in our patients. The benefits here outweigh the risk.

Another potential counterargument may then be, “Well, why can’t I just continue to do what I do (e.g., teach relaxation skills and/or teach children to focus on “positive” thoughts), given that these strategies are less risky and are also beneficial to my patients?” This is a great point. Relaxation and other strategies (e.g., changing anxious thoughts to positive thoughts) are important coping tools for anxious children. However, to maximize the effectiveness of our therapeutic work, these strategies should be taught alongside exposures. This allows children to practice such coping tools in real-time while they are doing an exposure during the treatment session. Therefore, instead of telling our patient to “practice slow breathing the next time you are anxious,” we get to witness the patient practicing slow breathing in real time while s/he is anxious. This allows us to provide live feedback on the child’s use of the skills (e.g., “try breathing even slower”) while they are in an anxiety-provoking situation. By receiving such feedback while they are in an anxiety-provoking situation, the skill is more likely to generalize to when they confront anxiety-provoking situations outside of the session (compared to practicing the skills in-session while they are calm/not anxious).

Myth #2: Exposures Damage the Therapeutic Relationship

This one was a big concern for me. I feared that if I pushed children into confronting distressing situations, they would resent me, hate coming to therapy sessions, and then convince their parents to take them out of therapy. However, after conducting hundreds of exposures with my patients, this has never happened. Not even once. In fact, by the end of treatment, many of my patients have reported that they are happy that they completed exposures as part of treatment. They say that they are proud of themselves for completing the exposures, and have reported “feeling brave” after the sessions. I’ve even heard patients say, “I didn’t think I could do it, but I did, and it wasn’t so bad!”

This is not to say that I have never been met with resistance when planning or bringing up the idea of exposures. Usually that is addressed by patiently re-explaining the purpose of why we’re doing the exposures, in a way the child understands. But overall, based on my experience, I believe that as long as the therapist conveys empathy/understanding towards the patient’s fears (e.g., “I understand how scary this might feel for you”), remains consistent in encouraging the patient to face his/her fears (e.g., “It’s okay if that was too hard this time, let’s talk about it and then see if we can try again”) and demonstrates a sense of pride when the patient attempts or successfully completes an exposure (e.g., “Nice job facing your fear! That was so brave!”), the therapeutic relationship tends to stay intact.

But don’t just take my word for it. Research also shows that “introducing exposures into treatment does not damage the therapeutic relationship”³.

Myth #3: Children Are Unable to Foresee the Benefits of Exposures

A third major concern that I had was whether younger children (i.e., as young as 6 or 7 years old) would be able to understand the purpose and rationale for doing exposures. I worried that children would consider therapy a “scary” place and wouldn’t understand why I was asking them to confront their fears.

Contrary to my initial belief, most children can grasp the concept if explained in a developmentally appropriate manner. For example, for younger children, I give an example of a girl named Andrea who is very scared of puppies (first I make sure the child is not scared of dogs or puppies). I ask the kids,

“If Andrea is really, really scared of puppies, will she want to play with puppies, or stay away from them?”

Most will say “Stay away from them.”

“But are puppies actually scary?”

“No!”

“What will probably happen if Andrea goes up to a puppy?”

“I don’t know, maybe it will lick her and want to play.”

“Yes, that’s right, the puppy probably just wants to play. But if Andrea is scared of puppies, what does Andrea think will happen if she goes up to one?”

“She probably thinks it will bark at her or bite her, maybe.”

“Yes that’s probably exactly what she’s thinking! But will it?”

“Probably not.”

“Okay, so let’s say Andrea practices being brave one day, and goes up to a puppy. Like we just talked about, the puppy just licks her on the hand a couple times and maybe brings her a toy. Makes sense, right?”

“Right.”

“So, once Andrea realizes that the puppy didn’t bite her or bark at her, will this make her feel more scared of puppies next time or less scared?”

“Less scared.”

“Yes, less scared! Now Andrea is less scared of puppies. So, the way Andrea became less scared of puppies was by facing her fears, going up to the puppy, and seeing that nothing bad happened (even though she thought the puppy would bark or bite). Does that make sense?”

“Yeah.”

“So in the same way, the work we will be doing together will involve being brave, facing our fears, and learning (like Andrea did) that even though we think something bad will happen, it actually won’t. But we’re going to do this in a slow, step-by-step way to make sure it’s not too scary.”

After this, I present a rationale for why we do it step-by-step, and let the child know that s/he plays a role in deciding which exposures to do. Most of the time, this rationale and an explanation of the up-and-down nature of fearful feelings are enough to help children understand the purpose of exposures.

Tips on Delivering Exposures

There is a right and wrong way to deliver exposures, so here are some (research-supported) techniques on how to reduce the chances of exposures going wrong:

Prior to beginning exposures:

- Ensure that the child and parent understand the rationale behind exposures

Just like therapists need to know how and why exposures work in order to feel comfortable delivering them, children need to know how and why exposures work so they can feel more comfortable practicing them. See the example above on how to explain the rationale for exposures. Keep in mind that the type of explanation should match the child’s developmental level.

- Seek child and/or parent input during the construction of the fear ladder

The child and parent should be a part of the treatment planning process. Allowing child and parent input can make exposures seem less intimidating, and allow children a sense of control over their treatment. Work together to determine a treatment goal and ensure that the exposures gradually move toward and reach that goal. “Remind children and parents that the exposures should ideally elicit a moderate amount of fear” (not too little, and not too much).

During exposures:

- Track the child’s fear ratings immediately before, during, and immediately after the exposures

Tracking the child’s fears can be done by obtaining a number from a scale of 0-10 of how scared the child is feeling. There are multiple benefits to tracking the child’s fear ratings throughout the exposures. From the therapist’s perspective, tracking the child’s fear ratings can provide helpful insight into whether the exposures are “too easy” or “too difficult.” Fear monitoring can also provide insight into whether the fear is moving in the anticipated direction (with fear ratings highest before the exposure and lowest after the exposure). From the child’s perspective, fear monitoring can provide “evidence” that the anticipation of the exposure tends to make him/her feel more scared than the exposure itself.

- Try to minimize distractions

In order to maximize the effectiveness of exposures, the child should enter the exposure with some level of fear and anticipation that something negative/dangerous will happen. While in the exposure, the child should still experience some fear and think about what it is s/he is afraid will happen. After the exposure, the child should realize that the feared outcome did not happen.

If the child is distracted during the exposure (i.e., doing anything that would prevent him/her from realizing and s/he is scared and fearful of some outcome), then the effectiveness of the exposure goes down. It is better for the child to confront the anxious feelings and realize that “I was scared and thought something bad would happen, but everything still turned out okay” versus “I wasn’t scared because I was distracted, but yes, nothing bad happened”.

After exposures:

- Praise the child’s efforts

Given that exposures can be temporarily distressing to children, it is important to “acknowledge the child’s bravery for attempting to face his/her fears”. Praise should be given when the child successfully completes an assigned exposure, or when the child makes any effort to complete the exposure (even if completion of the exposure is unsuccessful). Praising the child allows the child to feel a sense of accomplishment, reinforces continued practice of exposures, and can also aid in maintaining the therapeutic relationship.

- Help the child articulate what s/he learned from doing the exposure (i.e., that what s/he feared was going to happen, did not happen)

For exposures to be successful, the child should be able to articulate that the feared outcome did not occur. Therapists can facilitate this conclusion by explicitly asking, “What did you learn from this practice?” For younger children, the question can be framed as, “What did you think was going to happen before you went into the dark room?” “Did that end up happening?” “What actually happened?”

Stephanie’s Messy Hair

Stephanie (name and identifying details changed) was a 10-year old girl who had previously been diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. At the start of treatment, Stephanie and her mother reported that Stephanie avoided asking or answering questions in class, initiating or joining in peer conversations, and speaking to adults (e.g., waiters) because of excessive fear of appearing “stupid” or “weird”. Stephanie’s mother also reported that she took 30 minutes to fix her hair in the morning, which often resulted in arriving late to school and her mother arriving late to work. Stephanie reported that the reason she spent 30 minutes on her hair was because she was afraid other people would make fun of her if her hair was messy.

Stephanie’s main treatment goal was to be able to initiate and join conversations with other kids in school and extracurricular activities. Stephanie and her mother reported that a secondary treatment goal was to decrease the amount of time it took Stephanie to get ready in the morning, so that she and her mother were no longer late to school and work. Stephanie was on board with doing exposures to achieve her treatment goals (although she would initially try to avoid doing them), and demonstrated a good understanding of why we were doing exposures. I devised a “fear ladder” jointly with Stephanie and her mother. The first few weeks of exposure practice involved situations such as Stephanie saying “hello” and introducing herself to another adult and child in the clinic, asking questions to the front desk staff (e.g., “Can I borrow a pen?” and “What time is it?”), ordering for herself at restaurants, and saying “hi” to peers at school. Stephanie also practiced doing presentations in front of an audience of 3-4 people and engaging in back-and-forth conversations with other people for at least 5 minutes. By the ninth session, after completing several steps on the ladder, it was time for her to practice going out in public with messy hair. Here’s how the exposure went:

Therapist (Me): “Alright Stephanie, do you remember what was next up on the ladder for this week?”

Stephanie: “Yes, going outside with messy hair”.

Therapist: “That’s right. And how are you feeling about practicing that today?”

Stephanie: “Do we have to?”

Therapist: Smiles. “What do you think?”

Stephanie: Smiles and looks down. “Ok, I’ll try…”

Therapist: “Ok, wonderful! That’s all I care about, remember? That you try. So, going outside with your hair kind of messy: what makes that scary for you? What do you think will happen?”

Stephanie: “Wait. How messy is my hair going to be?”

Therapist: “We can decide that together. I was thinking of putting your hair in braids and having some hair falling out and sticking out in different places, because your mom told me about how you don’t like that. What do you think?”

Stephanie takes a deep breath and I notice her start to blush.

Stephanie: “Okay…”

Therapist: “I like how you just took a deep breath when you started to notice your fear go up. So now, back to my previous question: what makes this scary for you? What do you think will happen when we go outside?”

Stephanie: “Everyone will stare at me and come up to me and say, ‘Why is your hair so messed up?’”

Therapist: “Has that ever happened before, when your hair has been messed up?”

Stephanie: “No.”

Therapist: “Okay, so what do you think the chances are of that happening today?”

Stephanie: “I don’t know. I’m still scared it will happen.”

Therapist: “Okay, so as always, this will be our experiment. It’s never happened before, but let’s see if it happens this time.”

Stephanie nods.

Therapist: “So what’s your fear rating right now?”

Stephanie: “Seven.”

Therapist: “Ok, and what are some coping skills we can do to prepare us for this practice?”

Stephanie: “Deep breaths and positive thoughts.”

Therapist: “Exactly. What’s a positive thought you can tell yourself to feel more brave?”

Stephanie: “I’ve done this before and nothing’s happened.”

Therapist: “Great! And what if someone does stare at you? What did we talk about last time that you can tell yourself?”

Stephanie: “That I should say to myself, ‘So what?’”

Therapist: “Yes! You can ask yourself, ‘So what if they stare? Will it matter tomorrow that a random person stared?’ And will it?”

Stephanie: “No.”

Therapist: “Alright, let’s go.”

While we walked outside, Stephanie initially walked close behind me, hiding her face. After the first person walked by, I asked Stephanie, “Did that person stare at you?”

Stephanie: “No.”

Therapist: “Okay. Let’s keep experimenting and see what happens.”

As we walked around outside the therapy building, I asked a couple more times if she caught anyone staring. Stephanie reported that her fear rating decreased to a 4 in about 45 seconds. After another minute passed by, Stephanie reported that her fear rating was 2. Once we returned to the therapy room:

Therapist: “You did it! You walked around for 5 whole minutes with your hair messy, even though there were other people around. You stayed in the situation the whole time (even though you didn’t want to do it at first), and I even noticed that you moved from behind me to next to me! How did that feel for you?”

Stephanie: “Good. I was scared at first, but that wasn’t as bad as I thought it’d be.”

Therapist: “Great. So, what are the results from our experiment? Did anyone stare at you or ask you why your hair looked like that?”

Stephanie: “No, nothing bad happened.”

Therapist: “Yes, nothing bad happened. And what did you learn from today’s practice?”

Stephanie: “If I go outside with messy hair, people might not stare at me or come up to me.”

Therapist: “Great. And how do you feel knowing that you just faced your fear on something that was really scary, and stayed with it the whole time? You were at a 7!”

Stephanie: “I feel good, proud.”

Therapist: “Glad to hear it. I feel good and proud, too.”

Closing Comment

At first, I was intimidated by conducting exposures. I worried that exposures might make my patients’ anxiety worse, rupture the therapeutic relationship, and that I would not be able to effectively explain the purpose of exposures to children. Despite these fears, my training experiences have led me to become a strong believer in their effectiveness in treating child anxiety.

Once I “exposed” myself to the delivery of exposures with children and adolescents, I quickly learned that what I was afraid was going to happen (e.g., their anxiety will get worse, the therapeutic relationship will be damaged) did not actually happen. After continuously conducting exposures in treatment sessions with my patients, I learned that exposures do not tend to have negative or dangerous consequences. (It also helps that decades of strong research evidence show exposures do not have negative consequences). So, for any therapists out there who treat children (or adults) with anxiety disorders, especially those new to the field, I encourage you to confront any fears, myths or preconceptions you might have about exposures (gradually, if you must) and join me in this beneficial and therapeutic practice.

Resources

1. Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Ebesutani, C., Young, J., Becker, K. D., Nakamura, B. J., … & Smith, R. L. (2011). Evidence?based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 154-172.

2. Whiteside, S. P., Deacon, B. J., Benito, K., & Stewart, E. (2016). Factors associated with practitioners’ use of exposure therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety disorders, 40, 29-36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4868775/

3. Kendall, P. C., Comer, J. S., Marker, C. D., Creed, T. A., Puliafico, A. C., Hughes, A. A., . . . Hudson, J. (2009). In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 517-525. doi:10.1037/a0013686.