This blog post is a rejoinder to my Psychotherapy.net article, Seven Mistakes in Clinical Supervision. Here, I start by expanding on mistake #4, which is the failure to monitor engagement levels in clinical supervision, and then provide a way to deal with this issue.

Once we are able to escape the trappings of the first three mistakes in clinical supervision by avoiding too much theory-talk, helping our supervisees in their circle of development, and teaching them to marry the use of outcomes and alliance data to guide the treatment process, we can turn to thinking about the actual engagement levels of our supervisees.

Like what you are reading? For more stimulating stories, thought-provoking articles and new video announcements, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Let’s ask ourselves, What is clinical supervision for?

Ultimately, the aim of supervision is to help therapists develop so that their clients may reap the benefits. Edward Watkins noted in his 2011 review of clinical supervision impact on client outcomes that “If we cannot show that supervision affects patient outcomes, then how can we continue to justify supervision? The benefits of supervision on supervisees alone are not necessarily sufficient.”

And in order to ensure optimal learning benefits for our supervisees, we need to keep our eye on the ball regarding engagement level in supervision. As I previously mentioned, eliciting feedback from clients sounds simple in theory, but is not an easy thing to do in practice. In supervision, paradoxically, it can be even harder to give and receive feedback, given that there might be overlapping roles or a collegial relationship outside of the supervision context. Given this, I would argue that all the more, some kind of formal and systematic procedure for monitoring the engagement levels—whether the supervisory work is “on-track” or “off-track”—is necessary.

Here’s How

Instead of leaving it to some type of bi-annual or annual review—which is often too late—I propose that supervisors formally elicit feedback at the end of every consult. This allows real-time calibration so that the learner’s feedback can be fed-forward into the subsequent supervision sessions.

Now, I don’t know about your part of the world, but here in Australia, when we ask, “How has it been for you?” we typically get the response, “All good!” The aim here is to get nuanced feedback that can help you adjust and refine the process of supervision for that particular supervisee. This is why, not unlike the process of asking clients for feedback, I recommend that supervisors learn to take a pitstop near the end of a consult and use some form of engagement tool. This provides some distance and reflection for the supervisee to think it through.

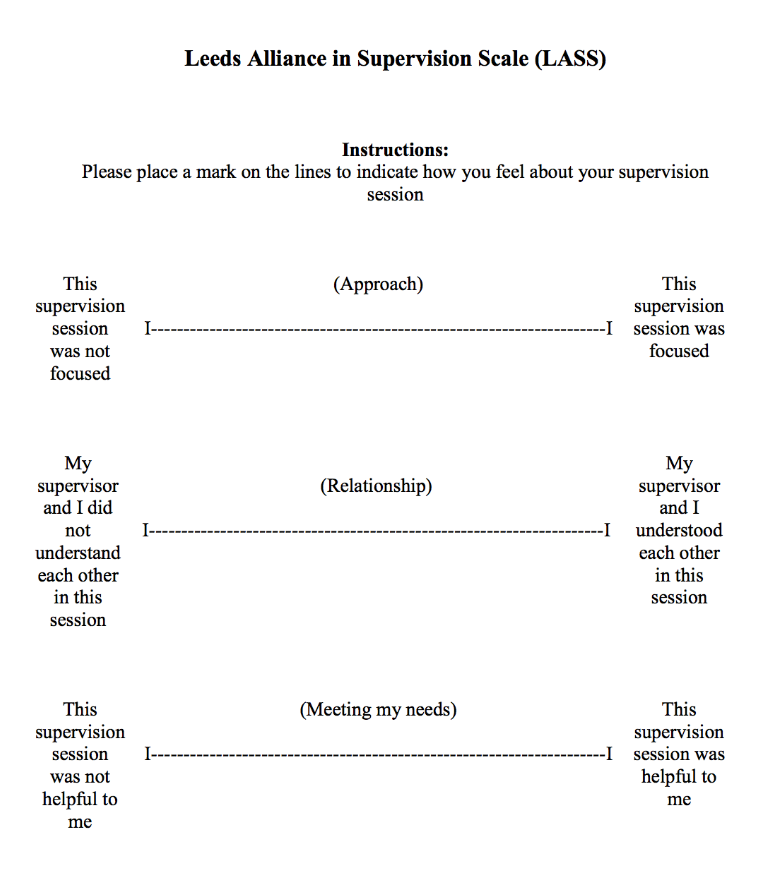

An example of a supervision engagement inventory, The Leeds Alliance in Supervision Scale (LASS)

How Do You Know the Effectiveness of Your Supervision?

Let’s circle back to the question that we asked ourselves earlier, what is clinical supervision for? If client improvement is the primary reason for clinical supervision, monitoring supervisee’s engagement alone is not sufficient. We also need to monitor the effects of supervision on client outcomes.

This can happen on two levels:

1. Single client outcome, based on the case discussion in supervision.

Take notes on what helped your supervisee, and what barriers were faced in their attempts to implement the ideas discussed in supervision.

2. Improvement in supervisee’s overall performance.

Supervisors have a real opportunity to influence when they learn to look at the data, spot patterns and help supervisees figure out what to work on that is influenceable and predictive of improving their outcomes.

References:

Wainwright, N. A. (2010). The development of the Leeds Alliance in Supervision Scale (LASS): A brief sessional measure of the supervisory alliance. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. University of Leeds

File under: The Art of Psychotherapy